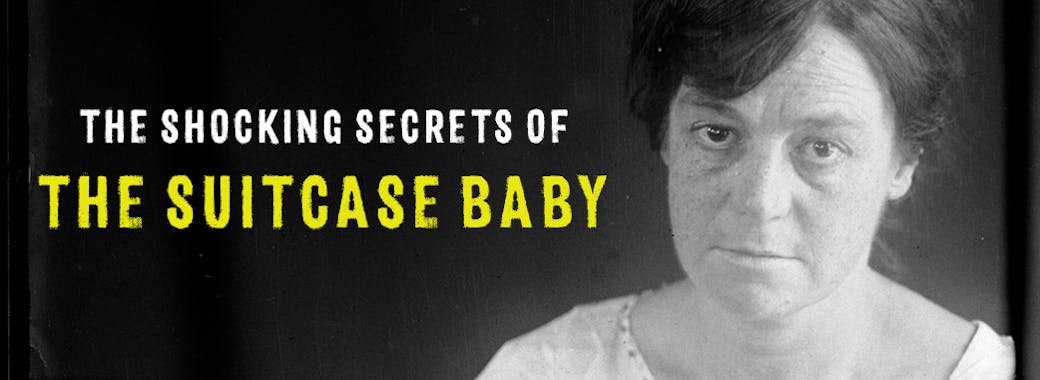

The Shocking Secrets of The Suitcase Baby

FRIDAY 16 FEB, 2018Tanya Bretherton discovered the jazz age was not all glitz and glamour when researching her new book THE SUITCASE BABY.

The fascination with true crime stories is not new.

I had always assumed that the morbid fascination with violent and tragic true crime stories was a social trend that emerged later in the twentieth century. Some argue that the publication of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood in the mid-1960s represents the birth of the true crime genre. Others argue that the growing interest in criminology and profiling has fuelled public interest in true crime. Sensationalist news stories that used the term ‘serial killer’ for example emerged post-1970s, and soon became part of mainstream vernacular. For these reasons I had always thought true crime was a very recent genre of entertainment, and perhaps part of modern society’s attempt to understand the darker parts of the human psyche.

During the process of researching The Suitcase Baby I began to realise that although the term ‘true crime’ may not have existed in the 1920s, public delight in criminality and the macabre has existed for a very long time. Stories which provide an overly detailed account of very gruesome criminal events filled the pages of 1920s newspapers, but also news reports going back into the nineteenth century as well. Newspaper editors have always devoted a huge amount of copy to the reporting of criminal events and the moral and legal implications arising from them. Murder and mayhem certainly sells newspapers today, but the same could also be said two hundred years ago.

Sydney’s Suitcase Baby experience was not unique

There is no doubt that Sarah’s story is shocking. The act of a mother killing a child is unthinkable - a taboo. During the process of researching The Suitcase Baby, I was even more shocked to discover that Sarah’s child was not alone. Many women made the terrible decision to murder and discard their babies not just in the 1920s, but in the decades preceding. Sarah’s tragic decision may have been uniquely sad, but it was certainly not unique in statistical terms.

The problem of infanticide was also not unique to Sydney. Dead babies were discovered in public places across all of the metropolitan capitals and in regional country towns too. Suffocated and strangled newborns were found in the poorest parts of cities and it was often assumed that economic desperation had led women to do the unthinkable. However, many dead babies were also found in the affluent suburbs. The shame and disgrace faced by women with illegitimate children was universal.

Other eerily similar patterns are associated with infanticide and the disposal of children at the turn of the twentieth century. Water often featured. While in Sydney, babies may have been thrown into the harbour, in Melbourne they were found on the banks of the Yarra. Public transport also often played a role. In Sydney, murdered newborns were found on trains, while in Melbourne and Adelaide they were found on trams and at tram stops. Most shocking of all, dead children were often found by children. Because many babies were discarded in public places (parks, vacant tracts of land between buildings, and bushland), children were often the ones to discover the bodies of babies. Children, in search of adventure and keen to explore the city in the early morning, often stumbled upon dead babies wrapped in newspaper, in petticoats or towels, who had been secretly disposed of under cover of darkness the previous evening.

The jazz age was not all glitz, glamour and Gatsby

While researching The Suitcase Baby I discovered that I had a lot of preconceived ideas about the 1920s and the jazz age which were not particularly representative of the experience of most women. When I think of jazz age I see flappers. I imagine women asserting themselves and challenging social conventions – particularly those surrounding sex. Stories I had read about jazz age Sydney prior to researching The Suitcase Baby seemed to affirm these very stylised ideas about the hedonism of the inter-war years. The 1920s in Sydney also produced some very famous women criminals. During the infamous razor gang wars of the inner city, women emerged as key protagonists. Kate Leigh and Tilly Devine were strong, gutsy and brassy broads – seemingly unafraid of the consequences of flouting social convention. Sarah Boyd’s story in The Suitcase Baby presents us with a very different narrative of jazz age life for women. To look at a photo of Sarah it is all too clear there is very little fight left in her.

For men who engaged in sex outside of marriage in the 1920s, the social and economic risks were comparatively low. For women, the stakes were higher. If a pregnancy resulted, men could simply ‘shoot through’ and although they could be legally charged with desertion, they had to be found first. By comparison, women faced a much tougher set of immediate social and economic consequences. Women who attempted to live openly as single mothers very quickly became destitute because they were shunned by employers, family and society. In the absence of any form of social welfare support and without child care, women faced grim prospects indeed.

The research I undertook for The Suitcase Baby was fascinating because it became about so much more than just one woman’s story. Sarah took risks and she challenged social norms surrounding marriage and family but she paid a huge price for it, and so did her children. Unfortunately, many women at the time also found themselves in similarly terrible, and ultimately tragic predicaments.

Tanya Bretherton has a PhD in sociology with special interests in narrative life history and social history. She has published in the academic and public sphere for twenty years, and worked as a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sydney for fifteen years. THE SUITCASE BABY is out now.

Related news

loading...

loading...

Writing Lillian Armfield: A gallant female role model for new generations

How Leigh Straw's goddaughter inspired her to search for a story.

loading...

loading...

5 Minutes With...Tanya Bretherton

THE SUITCASE BABY is true history and an unforgettable tale that moves at the pace of a great crime novel. Get to know author TANYA BRETHERTON in less than a minute!

loading...

loading...

Stop what you’re reading. These Australian set crime novels need to be next on your list.

The diverse Australian landscape is the perfect setting to cover up a crime, unravel a mystery or stay hidden. Discover what Maximum Sentence titles you should be reading next.

loading...

loading...

5 Minutes With ... Leigh Straw

Dr. Leigh Straw is an academic, historian and writer. We steal 5 minutes of her time to chat about her latest book on Australia's first female detective, Lillian Armfield, who took on Tilly Devine and the Razor Gangs!

loading...

loading...

Revelation by Sarah Ferguson and Tony Jones to be published by Hachette Australia

Acclaimed journalists and husband and wife, Sarah Ferguson and Tony Jones, team up for the first time in their multi-award-winning careers to write Revelation, the book behind the groundbreaking ABC TV series.

.png?auto=compress&w=150&h=60&fit=crop&fm=jpg)

.png?auto=compress&w=150&h=60&fit=crop&fm=jpg)